Click here to download these FAQs as a Word document, or here for a shorter version

The following terms are used below:

- “muni” is short for a municipal electric utility, of which 41 now exist in Massachusetts; a muni is also called a municipal light plant, municipal lighting authority or electric department

- “IOU” denotes a Massachusetts investor-owned utility, Eversource (formerly NStar and Western Mass Electric)), National Grid or Unitil; in Massachusetts State law, “owner” or “distribution company” also denote an IOU

- “legislation” means Bill H869 filed by 20 legislators for the 2011-2012 legislative session.

- “DPU” is the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities, the IOUs’ State regulator.

These 41 questions and assertions by IOUs are addressed below (please scroll down):

1. Massachusetts State law already spells out a process to form a muni, so why is this legislation needed?

2. What else does the legislation do?

3. How large is a typical muni?

4. A municipality would lose the local taxes the IOU pays if it replaces the IOU with a muni.

5. Will this legislation promote economic development in Massachusetts?

6. Why do munis charge so much less than IOUs for the same electricity?

7. What effect does the legislation have on energy efficiency programs?

8. Would a new muni’s large commercial and industrial customers have a choice of power supplier?

9. Are munis good for employees?

10. How will the legislation impact unions?

11. How much do top executives earn at IOUs and munis?

12. Does this legislation effectively subject IOUs to a taking of their property without just and reasonable compensation?

13. Can DPU assess the fair market value of an IOU’s assets?

14. So the price set by DPU under the legislation for the IOU’s assets would not take into consideration the IOU’s loss of future sales?

15. Would the price set by DPU under the legislation for the IOU’s assets take into consideration the physical reconfiguration of the IOU’s infrastructure?

16. How will the IOU be reimbursed for the capital improvements made between the time of the DPU price determination and the time of closing with the muni?

17. Is this legislation akin to government taking over utilities in Massachusetts?

18. Are munis a relic of the past, not part of the future?

19. Aren’t conditions today very different than those in the early 20th century, when the Massachusetts munis were formed?

20. Why were no munis formed in Massachusetts since the late 1920s?

21. But even after a community forms a muni, there is still only one utility, and no real competition. So how has competition increased?

22. IOUs claim they are dedicated to satisfying their customers, so why would a municipality want to form a muni?

23. Since Town-owned electric systems are not accountable to state regulators, won’t customer service deteriorate?

24. How can munis match the IOUs’ resources in disasters, including access to crews from sister companies in New England and elsewhere?

25. Don’t large IOUs achieve economies of scale unavailable to municipal systems?

26. If munis combine efforts and contract for services from third parties, don’t we end up with another IOU?

27. Don’t IOU serve an important role as active members of the communities they serve?

28. Do communities have the expertise to run a muni?

29. Aren’t the many complex logistical issues that must be addressed before a community creates its own muni overwhelming?

30. What if a muni fails?

31. Some munis are very well run, but couldn’t other munis make mistakes?

32. How can munis navigate the deregulated wholesale power markets?

33. Would the formation of new munis harm the remaining customers of the IOU?

34. Are the costs to distribute electricity lower in towns with high average incomes and low population diversity?

35. Could Massachusetts end up with 351 different electrical systems – one per municipality – and numerous interfaces among them, causing problems with worker safety and service?

36. Losing pieces of the infrastructure will lead to a balkanized distribution system. Customers in adjoining communities may not be treated equitably.

37. Without IOUs and the strategic commitment of large capital resources, the maintenance of distribution systems would be haphazard and disjointed.

38. Distribution systems owned by local governments do not contribute to the overall maintenance of the nation’s electric grid.

39. How does the legislation impact low-income customers?

40. Does the municipal purchase of streetlights show a disparity in the quality of service and asset maintenance under municipal ownership?

41. Does the existing mechanism for municipalities to require IOUs to underground their service work well?

ANSWERS

1. Massachusetts State law already spells out a process to form a muni, so why is this legislation needed?

Massachusetts General Laws (MGL) Chapter 164, Section 43 already defines the process a municipality must follow to form a muni, by acquiring the IOU’s assets at a fair price to be determined by DPU.

The law, written about a hundred years ago, states towards the end of the process “[…] Should the owner not file such acceptance and tender within the time so limited, the town may proceed to construct or otherwise acquire a municipal plant without further attempt to acquire the plant of such owner […]” where “owner” refers to the IOU serving the municipality.

While a municipality can start the process of forming a muni, and pursue it through the determination of the sale price by DPU, the incumbent IOU can refuse to sell its assets at the end of the process (i.e. “not file such acceptance and tender within the time so limited”). In today's environment (as opposed to a century ago when an “owner” operated perhaps a half-dozen poles in the center of town for streetlights), the remedy now in MGL Chapter 164, Section 43 (“the town may proceed to construct [its own electricity distribution network, separate from the IOU’s]”) is no longer economically practical, effectively allowing the IOU to block any new muni. In fact, except for the Devens muni formed by special legislation in 1996, no muni has been formed in Massachusetts since 1926.

This legislation removes the IOU’s ability to block a new muni, achieving the Legislature’s goal when MGL Chapter 164, Section 43 was enacted, that a municipality can operate its own muni. The legislation replaces the now obsolete remedy – if the IOU refuses to sell its assets, the municipality can start a second electric network – with a clear requirement that the transaction must go through once DPU has determined the fair price the municipality must pay for the IOU’s assets.

2. What else does the legislation do?

Besides removing the ability IOUs now have to block any new muni, the legislation keeps the MGL Chapter 164, Section 43 process essentially unchanged.

The legislation updates time lines that are not clear or appropriate today, adds a review by DPU of the economics of the proposed new muni (to prevent a municipality from engaging in this complex process without having done its homework), limits to three per year the number of new munis DPU must review (to limit the workload for DPU and to ensure a deliberate process), stipulates that customers of new munis will be able to choose their competitive power supplier – like IOU customers do – and transfers the franchise from the IOU to the new muni after the municipality has purchased the IOU’s assets.

3. How large is a typical muni?

Massachusetts’ 4 IOUs serve 85% of the State’s population. The remaining 15% of our population is served by 41 munis created between 1889 and 1926 (plus Devens, a special case, in 1996).

In 2007, the largest Massachusetts muni was Taunton (sales of 718.2 million kWh to 35,900 customers; $93.6 million in revenues) and the smallest was Chester (sales of 5.5 million kWh to 650 customers; $670,000 in revenues).

Concord (sales of 181.7 million kWh to 7,700 customers in 2007; $19.4 million in revenues) is a mid size muni. The Concord muni employs 32 people (including 11 linemen), has 42,000 square feet of offices, garage and warehouse and owns 37 vehicles or trailers (including 8 bucket trucks).

4. A municipality would lose the local taxes the IOU pays if it replaces the IOU with a muni.

Not true. This incorrect assertion is often made by IOUs to scare municipal officials. While munis do not pay local taxes, most munis pay instead to their municipality a PILOT (Payment In Lieu Of Taxes) comparable to the local taxes an IOU would pay on the same equipment.

In 2003, the most recent year for which the US Department of Energy’s Energy Information Administration has data available, a sampling of Massachusetts munis that made PILOT payments to their municipality is: Braintree $930,275, Concord $340,000, Holyoke $808,320, Hudson $268,163, Littleton $250,000, Mansfield $480,000, Middleborough $265,112, Peabody $1,613,344, Reading $983,294, Wakefield $240,109 Wellesley $1,000,000, Westfield $200,000 (Source: EIA Form 412, Schedule 5, line 9).

Any municipality that establishes a new muni under this legislation would ensure that a PILOT is set at an appropriate level so the municipality does not lose any revenues.

5. Will this legislation promote economic development in Massachusetts?

Yes, the legislation will promote economic development because it will put downward pressure on the IOUs’ electric rates for residents, businesses and municipalities across the State, lowering the cost of doing business in Massachusetts. This is because IOUs will have an incentive to lower their rates and improve service, to avoid “losing” parts of their service territory to new munis. One of the reasons Bristol Myers Squibb made a large investment in Devens – which has a muni – is that Devens offers attractive electricity rates (Boston Globe 6/9/06).

Each year, NStar charges residents about $400 million more, and businesses and public facilities (schools, hospitals, etc) about $300 million more than munis charge for the same electricity. NStar’s high rates effectively impose a $700 million “drag” on the Massachusetts economy, the size of which would diminish once this legislation is enacted, because IOUs would work harder at becoming more efficient, thereby reducing their rates.

2007 electricity costs at several dozen Massachusetts stores of a major supermarket retailer served by NStar, National Grid and munis – each store using about 2,500,000 kWh of electricity per year (as much as 400 homes) – were 11.3 cents per kWh from munis, 13.0 cents per kWh from National Grid (14.7% more than munis) and 14.5 cents per kWh from NStar (28.8% more than munis). If all stores paid the lower muni rates, this retailer’s electricity costs would have been cut by $5 million.

2006-07 electricity costs for Boston area high schools were 9.2 cents per kWh from munis and 18 cents per kWh from NStar. A school system would save $500-600,000 annually if its electric rates were at the level charged by munis instead of NStar, enough to hire 6-8 additional teachers at no cost to taxpayers.

6. Why do munis charge so much less than IOUs for the same electricity?

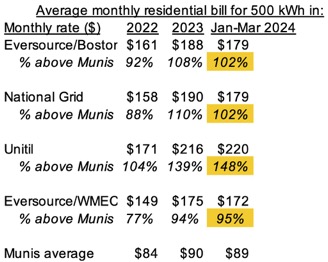

It is difficult to account for all the very large differences in rates. Recent residential rates for 500 kWh/month were:

Source: MMWEC surveys for residential usage of 500 kWh per month

In the first half of 2009, NStar and Unitil were charging $36-$38 more per month for the same electricity than the average muni. Some of the factors sometimes offered for these price differentials are very small or non-existent.

Less than $1.50 is because existing munis do not have the same charges as IOUs for energy conservation and renewables, for which IOUs charge 0.3 cent/kWh (or $1.50 for 500 kWh per month). Various existing munis have various types of energy-efficiency and renewables programs. New munis formed under this legislation would spend at least as much as the IOUs on clean energy.

A similar amount of the IOUs’ regular residential rates may be due to the discount offered to low-income customers.

Municipal utilities typically pay more to their local government (as payments in lieu of taxes or other transfers) than IOUs pay in property tax. These payments actually raise muni rates, compared to IOUs.

After accounting for the differences in funding of energy-efficiency, renewable and low-income programs, and even ignoring the munis’ greater support for local government, NStar and Unitil still charge $30–$35/month more than munis. The remaining rate difference is the result of a combination of factors, which we cannot quantify individually:

- IOUs pay dividends to their shareholders, but munis only have to balance their budget

- the cost of borrowing is higher for IOUs than for munis, which use low-cost 4%-6% interest municipal bonding

- IOUs have highly paid executives and several levels of management, while munis are small, lean operations

- munis have consistently maintained their infrastructure better than IOUs

- some munis combine billing for electricity with their municipality’s billing for water and sewer

- munis are generally more efficient, with linemen who know the local network very well, while IOUs experience higher personnel turnover, and have fewer employees.

7. What effect does the legislation have on energy efficiency programs?

New munis would collect the same energy efficiency and renewable charges that IOUs collect (currently $0.003 per kWh, or $1.50 per month for a typical 500 kWh residential customer). The munis would be required to provide energy-efficiency programs at least as good as those of the IOUs. In addition, the munis would participate in the statewide promotion of renewables.

8. Would a new muni’s large commercial and industrial customers have a choice of power supplier?

Yes, the legislation clearly states that the large customers of a new muni would have access to the competitive market.

9. Are munis good for employees?

Yes. Most IOU employees are unionized, and their compensation and benefits are determined by contracts negotiated by the union and the company. Most munis are also unionized, and their compensation and benefits are set the same way.

In addition, IOUs will feel competitive pressure to improve performance as a result of the legislation. That will require that IOUs hire more employees to perform preventive maintenance, remove double poles, respond to customer and municipal queries, repair damaged equipment, and otherwise keep customers happy: this legislation will create new jobs.

10. How will the legislation impact unions?

Unions would benefit from the legislation. Most muni employees are unionized, as are most employees of municipalities. Muni cost advantages are not due to lower union wages or to the absence of unions altogether: unionized Braintree linemen earn more than unionized NStar linemen.

Moreover, since munis have more linemen than IOUs, the formation of new munis will add jobs overall. And because the legislation will create pressure on IOUs to improve service – which requires additional staff –, IOUs are likely to hire more (unionized) employees once the legislation is enacted.

But the new jobs may be in different unions. NStar’s linemen are in the Utility Workers Union of America (UWUA), but munis also have other unions besides UWUA, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), etc.

11. How much do top executives earn at IOUs and munis?

NStar’s top five executives received $17 million-$21.7 million in total compensation annually in 2005-2007, according to the Boston Business Journal and NStar’s annual proxy statements DEF 14A, as follows:

Executive 2005 2006 2007

Thomas J. May, Chairman, President & CEO $11.7 million $11.6 million $9.7 million

James J. Judge, SVP, Treasurer & CFO $2.8 million $3.5 million $1.7 million

Douglas S. Horan, SVP Strategy, $2.8 million $3.6 million $2.8 million

Law & Policy, Secretary & General Counsel

Werner J. Schweiger, SVP Operations $1.1 million $1.8 million $1.5 million

Joseph R. Nolan, Jr., SVP Customer $1.5 million $1.2 million $1.3 million

& Corporate Relations

TOTAL NStar's top 5 executives $20.0 million $21.7 million $17.0 million

A report on NStar's top executives 2009 compensation appeared in the Boston Globe, based on NStar's proxy statement for 2009 summarized here which show similar levels of compensation in 2008 and 2009.

Unitil’s top five executives received $2.6 million in total compensation in 2007 (according to the Sentinel & Enterprise from SEC filings):

Robert G. Schoenberger, Chairman of the Board, CEO and President: $1,179,819

Thomas P. Meissner Jr., SVP and COO: $408,319

Mark Collin, CFO, SVP and Treasurer: $394,977

George Gantz, SVP: $367,306

Todd Black, President of Usource (an Internet-based company, subsidiary of Unitil): $264,762

Unitil's proxy statement for 2009 shows similar levels of compensation in 2008 and 2009.

Muni General Managers earn $110-150,000 per year, for example, in 2008 in Concord $124,257 and in Belmont $137,775, and in 2005 in Braintree $135,492, in Hingham $123,173 and in Hull $104,430.

12. Does this legislation effectively subject IOUs to a taking of their property without just and reasonable compensation?

No. The legislation requires that the municipality pay what DPU determines the IOU’s assets (poles, wires, substations, transformers, sectionalizers, capacitor banks, etc necessary to distribute electricity within the municipality) to be worth.

DPU would set the price as the unrecovered investment of the IOU, typically in the tens of millions of dollars, depending on the amount of equipment installed in the municipality and its age. The IOU would receive a one-time payment equivalent to what the IOU would earn from customers in the municipality if it continued to serve them, plus other “reasonable compensation”. DPU’s methodology to set the price is similar to what is already in MGL Chapter 164, Section 43, and to what DPU does when it approves an IOU’s rates regarding the component of the rate that compensates the IOU for the value of its assets. The muni would be responsible for paying off the bonds used to purchase the IOU’s assets.

13. Can DPU assess the fair market value of an IOU’s assets?

Yes. DPU would determine the fair value of the IOU’s assets, using utility rate-setting rules. DPU determines in each rate case the net value on which the IOU is allowed to earn a return, and that the IOU will be allowed to depreciate and recover from customers. To determine the purchase price, the DPU will apply the same principles to the plant in a particular municipality. DPU conducted this type of analysis in the 1990s, to resolve a dispute between the Hudson muni and the Town of Stow, which is also served by the Hudson muni.

In addition, the legislation allows DPU to include “any other components required to provide reasonable compensation to the distribution company” to ensure that the IOU is compensated fairly for its assets.

14. So the price set by DPU under the legislation for the IOU’s assets would not take into consideration the IOU’s loss of future sales?

Actually, the price would be equivalent to the IOU’s lost revenue stream. IOU rates are set to allow them to earn a fair return (defined as the cost of the debt and equity capital) on the original cost of plant investment less accumulated depreciation. The IOU’s rates are set to recover expenses and that return. The purchase of the IOU’s assets in a municipality at depreciated original cost relieves the IOU of the need to raise the associated capital (and gives the IOU cash to invest in other IOU operations or unregulated businesses), as well as relieving the IOU of the associated expenses of serving customers in the municipality. The price paid, and the savings in expenses, thus fully cover the revenues the IOU loses from the sale of the plant, and actually increases IOU cash flow at the time of the sale.

15. Would the price set by DPU under the legislation for the IOU’s assets take into consideration the physical reconfiguration of the IOU’s infrastructure?

Yes. DPU would approve a least-cost severance plan. In general, there will be little reason to reconfigure the physical infrastructure, other than adding a few meters where major distribution lines run into or out of the new muni service territory. In addition, the legislation allows DPU to include “any other components required to provide reasonable compensation to the distribution company” to the price the municipality must pay to ensure that the IOU is fairly compensated.

16. How will the IOU be reimbursed for the capital improvements made between the time of the DPU price determination and the time of closing with the muni?

In streetlighting transfers, the settlements and DPU orders have provided for updates for additions and depreciation until the closing date. The contracts under which IOUs divested their generation had similar terms.

While the DPU valuation of a distribution system can provide for such reconciliation under the current language of the legislation, this point could be clarified in the Committee markup of the bill.

17. Is this legislation akin to government taking over utilities in Massachusetts?

No, the opposite is true. Massachusetts IOUs have not faced any competition in the provision of electricity distribution services for many decades, because the now obsolete, century-old language in MGL Chapter 164, Section 43 allows an IOU to block any new muni. As regulated monopolies, IOUs do not operate in a competitive marketplace, nor can they charge whatever price they want; rather, IOUs need DPU’s approval for their rates.

Also, nothing prevents a muni to sell its assets back to an IOU, for example if the community decides that an IOU would do a better job than the muni.

The legislation does not require that any new muni be formed. Rather, by making the option to form a muni practical again, the legislation effectively reintroduces a form of “competition” for IOUs, which no longer exists, As a result, IOUs will have a strong incentive to improve their service, lower their rates and become more responsive to the needs of local communities, to avoid municipalities becoming so upset with an IOU as to initiate the process to form a muni.

18. Are munis a relic of the past, not part of the future?

Not at all. Between 1981 and 1989, eight new public-power systems were formed, serving from a few hundred to 16,500 customers each: Massena Electric Department, NY; Trinity County Public Utility District, CA; Emerald People’s Utility District, OR; Page Electric, AZ; Troy Light & Power, MT; Lassen Municipal Utility District, CA; Clyde Light & Power, OH; City of Santa Clara, UT.

Since 1996, another eight new public-power systems have been formed, serving from a few hundred to a million customers each: Tarentum Borough, PA; Merced Irrigation District, CA; Ak-Chin Electric Utility Authority, AZ; Eagle Mountain, UT; Long Island Power Authority, NY; City of Hermiston, OR; Moreno Valley, CA; and Winter Park, FL. Another half-dozen or more public-power utilities have been formed to serve new or redeveloped areas (including in Massachusetts at the former Fort Devens in 1996). Territory previously served by IOUs has been acquired by public and customer-owned utilities, including the takeover of Bozrah Power and Light by Groton CT and of Citizens Utilities by the Vermont Electric Coop.

19. Aren’t conditions today very different than those in the early 20th century, when the Massachusetts munis were formed?

Yes. Some public power systems were established to bring power to communities that had little or no electric service. But others were established to reduce costs, improve service, and establish local control. Those remain important considerations for some communities.

Obviously, should conditions not favor a new muni over the existing IOU, in costs and service, no municipality will go through the trouble and expense of forming a muni.

20. Why were no munis formed in Massachusetts since the late 1920s?

There were a number of conditions that worked against public power from the 1920s through the 1980s. Most importantly, IOUs dominated transmission and access to cost-effective generation. Munis like Belmont, Wellesley, Norwood and Concord were forced to purchase all their power from the IOU, since no one else could sell to them. A series of anti-trust decisions and Federal regulatory decisions opened the transmission system to the munis, and the restructured wholesale power market eliminates any advantage the IOUs had in building large power plants.

Since the early 1990s, the most important obstacle to forming a new muni in Massachusetts has been the inability to require the IOU to sell its equipment.

21. But even after a community forms a muni, there is still only one utility, and no real competition. So how has competition increased?

The competition is between the IOU and the option for a community to form a muni, which this legislation provides. If and when the IOU loses the battle for the hearts and minds of its customers in one community, and the municipality forms a muni, the muni must prove itself to the public, or face the prospect that the municipality will decide to return to corporate management. The voting public would always have a choice of maintaining the muni, hiring an IOU to run the municipality-owned infrastructure, or selling the infrastructure to an IOU. Those are choices in distribution suppliers that IOU customers do not have now.

22. IOUs claim they are dedicated to satisfying their customers, so why would a municipality want to form a muni?

If IOUs indeed deliver on their claims, the municipalities they serve will have no reason to form munis, and IOUs should not oppose this legislation. By making the option to form a muni once again real, this legislation will encourage IOUs to offer better service, lower rates and better responsiveness to local needs so that their communities have no reason to start a muni. But if a municipality becomes sufficiently frustrated with the IOU’s high rates, poor reliability, bad service, lack of removal of double poles, inattention to aesthetics or other issues, this legislation provides an option other than keeping an unresponsive IOU as their sole electricity distributor.

23. Since Town-owned electric systems are not accountable to state regulators, won’t customer service deteriorate?

Not at all. Munis are directly accountable to the voters in the municipality. It is now well documented that muni customers believe that they are generally served very well.

24. How can munis match the IOUs’ resources in disasters, including access to crews from sister companies in New England and elsewhere?

Munis do the same thing as large IOUs, via mutual-assistance agreements with other munis.

Munis are better than IOUs at maintaining service and at restoring power after outages occur, as the December 2008 ice storm (munis restored power faster than Unitil and National Grid) or the sweltering summer of 2001 (munis fared better than NStar, which experienced widespread outages) illustrated. This is the result of the munis’ extensive preventive maintenance, network upgrades and higher staffing (munis have more linemen on staff than NStar as Boston University’s New England Center for Investigative Reporting has also documented).

25. Don’t large IOUs achieve economies of scale unavailable to municipal systems?

There are probably some economies of scale, but there may also be diseconomies of managing a large operation. Municipalities will need to take their size into account when analyzing the economics of forming a muni. Since munis systematically charge their customers less than IOUs, those economies of scale are outweighed by the economies of municipal ownership and by operational efficiencies for the existing munis. New munis may also choose to work in partnership with existing munis to share resources.

26. If munis combine efforts and contract for services from third parties, don’t we end up with another IOU?

No. Each town would retain the right to switch to another service supplier, or start providing the service itself. The legislation does not allow an established muni to serve territory in another community; it only allows a community to form a muni, which can then decide whether to contract with third parties for specific management, operations and maintenance services.

27. Don’t IOU serve an important role as active members of the communities they serve?

Such active relationships may help convince municipalities to remain with their IOU.

But munis are the communities they serve and tend to be more responsive to local needs than IOUs. While a muni General Manager is right in town, in constant reach of the Mayor or Selectmen, Town Manager, Town Meeting or City Council and ordinary residents, National Grid is headquartered in London, an ocean away; Boston-based NStar serves customers as far away as the Cape and Islands; Western Mass Electric is managed from Northeast Utilities headquarters in Berlin, Connecticut; and Unitil is headquartered in Hampton, New Hampshire.

28. Do communities have the expertise to run a muni?

The legislation requires a formal review by DPU of the municipality’s economic study of the feasibility of a muni. DPU would at that stage assess the municipality’s expertise. A municipality with insufficient expertise would not even be able to file with DPU anything substantive about forming a muni.

Because going through the process set by the legislation requires quite a bit of expertise, very few new munis are likely to be formed after the legislation is enacted.

A new muni would probably hire a third party (an existing muni, another IOU, or a consulting firm) to commission the system and gradually turn control over to muni employees. Alternatively, the new muni may enter into a long-term agreement to share management services with an existing muni, or with an IOU or with a company that operates electricity distribution systems.

29. Aren’t the many complex logistical issues that must be addressed before a community creates its own muni overwhelming?

Yes, forming a muni is a challenging, complex, expensive and lengthy process. But that does not make the legislation unimportant, or unworthy of support: without it, no new muni is possible.

The legislation makes the option to form a muni practical, without imposing that option on any municipality. Because the process is indeed very complex, very few new munis are likely after the legislation is enacted, perhaps 3-5 new munis over 20-30 years. But with the option to form a muni once again real, all Massachusetts electricity users will benefit because IOUs will have a strong incentive to improve their service, lower their rates and become more responsive to the needs of local communities. As a Boston Globe editorial put it, this legislation is “A promising bill […that] would restore some power to the consumer.”

30. What if a muni fails?

None of the 40 munis formed in Massachusetts between 1889 and 1926 (plus Devens in 1996) has ever failed. If a muni – or an IOU – was in trouble, it would have to raise its rates. Since muni rates are lower than IOUs’, that gives munis more “room” than IOUs in case of operational difficulties.

31. Some munis are very well run, but couldn’t other munis make mistakes?

Munis can and do make mistakes, just like IOUs. Many munis bought into the Seabrook nuclear plant, for example. Despite those mistakes, munis consistently provide lower rates than IOUs, and generally better service than most IOUs, for all classes of customers.

32. How can munis navigate the deregulated wholesale power markets?

Munis have mostly been able to keep their power-supply costs at or below the level of the IOUs. Since they have more flexibility, munis can structure their power-supply contracts to minimize costs and variability in costs. Munis engage the services of experienced industry consultants to help them secure power-supply contracts, much as IOUs and large customers do.

A majority of the large commercial and industrial power users in Massachusetts purchase generation services from the market, rather than their IOU. Even a relatively small muni will have a larger load than the bulk of those commercial and industrial consumers.

33. Would the formation of new munis harm the remaining customers of the IOU?

No. Electric customers in the remaining communities served by the IOU will be responsible for supporting the remaining distribution system of the IOU, after the muni has acquired the assets it needs to operate. The remaining communities would not pick up any additional costs. The new muni would pay for distribution within its own territory while the IOU would charge the remaining communities the costs of serving them.

34. Are the costs to distribute electricity lower in towns with high average incomes and low population diversity?

No. In fact, muni rates do not appear to be lower in affluent suburbs than in older industrial cities. Every study we have been able to find demonstrates that the higher cost communities would tend to be the suburbs, where low loads per mile of circuit result in higher distribution costs, compared with urban areas.

As a result, today, in NStar’s Boston Edison service territory, the less-affluent ratepayers (in Boston and Chelsea) are likely to be subsidizing suburban ratepayers (in Lexington). The communities that ultimately form new munis as a result of the legislation are likely to be determined more by the level of frustration with the IOU, than by differences in underlying costs of serving each community.

35. Could Massachusetts end up with 351 different electrical systems – one per municipality – and numerous interfaces among them, causing problems with worker safety and service?

No. There won’t be 351 different electrical systems. Most communities will not choose to form a muni because the process is so complex, expensive and lengthy, especially if the better IOUs maintain their service quality and the worse IOUs improve. If several towns in an area do form munis, they are likely to establish some form of cooperative under common management. For example, there has been interest in the three NStar-served Hanscom Area towns (Lincoln, Bedford, Lexington) in working with the existing Concord muni to have a four-town system sharing some of the overhead functions.

Second, the legislation requires that DPU approve a severance plan to ensure the coordination and efficiency of the electric distribution system, including as it is connected to the IOU-run system.

Third, Nebraska has 155 publicly owned systems serving 905,000 customers; each system serves on average 6,000 customers, at 5.5¢/kWh on average (2002). Nebraska has no particular problems with safety or service, and has chosen to maintain its all-public power system for nearly 60 years. Similarly, Tennessee has 87 public utilities, serving about 3 million customers.

36. Losing pieces of the infrastructure will lead to a balkanized distribution system. Customers in adjoining communities may not be treated equitably.

The legislation requires that DPU approve a severance plan to ensure the coordination and efficiency of the electric distribution system, exactly to deal with these concerns.

It is important to recognize that distribution lines frequently run from one utility service territory to another. For example, these situations are common in Vermont, which is served by over 20 utilities (some of which have disjointed pieces of service territory). A line from an IOU substation may serve some of the IOU’s customers, then run into the territory of a cooperative utility to serve more customers. The arrangements that work in Vermont and other states can work in Massachusetts, and already do for Massachusetts’ 41 existing munis.

37. Without IOUs and the strategic commitment of large capital resources, the maintenance of distribution systems would be haphazard and disjointed.

Munis generally have better reliability than IOUs (especially NStar and Unitil), so they obviously maintain their distribution systems well. The whole State of Nebraska is served by muni-like publicly owned utilities.

38. Distribution systems owned by local governments do not contribute to the overall maintenance of the nation’s electric grid.

New England munis pay the same rates for the use of the transmission system as IOUs, and thus contribute exactly the same amount to the overall maintenance of the nation’s electric grid.

39. How does the legislation impact low-income customers?

New munis are likely to take at least as good care of low-income customers as the IOU does. Muni rates are lower than rates from IOUs, which helps low-income customers. DPU could be given the authority to require a muni to adopt low-income discounts, and to approve them. The costs for IOUs from non-payment of electric bills by low-income customers are relatively small, so the loss of a few municipalities forming new munis would not substantially increase the low-income subsidy cost by the IOU’s remaining customers. In the unlikely event that the Legislature determines that municipalization was causing some major inequities in support for low-income customers, it could create a mechanism to spread such costs across all utilities, munis and IOUs, or authorize the DPU to do so.

The legislation does not require munis to offer discounts for low-income residents. Municipalities have been quite active in finding ways to assist low-income, elderly, and otherwise vulnerable residents, in terms of property-tax relief and other benefits. Each muni will be able to design assistance programs that best fit its circumstances, in response to local needs.

40. Does the municipal purchase of streetlights show a disparity in the quality of service and asset maintenance under municipal ownership?

Yes, and municipalities do better than IOUs. That is an excellent example of the disparity in quality of service between an IOU and municipal ownership. Municipalities that have purchased their streetlights have generally achieved better maintenance and faster service than they experienced with their IOUs, especially NStar, while saving money. Lexington, which pioneered the municipal purchase of streetlights, is very encouraged by those results and is interested in exploring the extension of the buyout to the entire distribution system, so that the Town can improve reliability and service for all customers, as it has for streetlights, while reducing electricity costs for residents, businesses and the Town.

41. Does the existing mechanism for municipalities to require IOUs to underground their service work well?

No. MGL, Chapter 166, Sections 22B and 22D provide that a municipality can require by ordinance or by-law that the IOU underground its distribution system in part or all of the municipality, with the costs borne by the ratepayers in the municipality through a surcharge (Section 22M). The “ordinance or by-law may specify in whole or in part the sequence which any utility shall follow in removing its poles and overhead wires and associated overhead structures” but the utility is not required to spend more than 7% of distribution revenues (Section 22D). (The 7% of distribution revenues for distribution utilities replaces the 2% of total revenues for the pre-1997 vertically integrated utilities.)

Nothing in that section requires the IOU to estimate the costs of the reconfiguration or to minimize the cost of reconfiguration. The municipality thus has no control over the cost of the undergrounding project, and has no way to determine the cost-effectiveness of the undertaking. Since the municipality does not know the costs of the project, and the IOU’s annual expenditures are capped by the law, the municipality cannot know when specific portions of the project will be completed, and hence cannot coordinate undergrounding with related work, such as water and sewer line maintenance and road-surface reconstruction.

None of these limits of municipal authority under Chapter 166 would be serious problems in dealing with a utility that wanted to cooperate with the municipality. Unfortunately, IOUs have not been cooperative, as evidenced by Bedford’s protracted problems with NStar in undergrounding the electric system in its town center (which ended up costing $3 million per mile), and Lexington’s inability to get any form of cost estimate or time schedule from NStar for undergrounding projects in its own town center.

In contrast, the Concord muni already has 40% of its network underground across town, and transfers another mile or so underground each year, at a cost of $600,000 per mile, paid by the muni’s budget. Undergrounding is effectively “free” for Concord residents because they pay 30-40% less to the Concord muni than NStar would charge for the same electricity, and undergrounding costs are paid via those low electric bills.