Cities Weigh Taking Electricity Business From Private Utilities

The Valmont power plant in Boulder, Colo. The city is considering creating one of the first new municipal utilities in years. Kevin Moloney for The New York Times

By DIANE CARDWELL Published: March 13, 2013

Across the country, cities are showing a renewed interest in taking over the electricity business from private utilities, reflecting intensifying concerns about climate change, responses to power disruptions and a desire to pump more renewable energy into the grid.

Boulder, Colo., for instance, could take an important step toward creating its own municipal utility, among the nation’s first in years, as soon as next month. A scheduled vote by the City Council comes after a multiyear, multimillion-dollar study process that residents, impatient with the private electric company’s pace in reaching the town’s environmental goals, helped pay for by raising their own taxes.

Environmental concerns have led officials of the City of Boulder, Colo., to look into forming a public utility. Kevin Moloney for The New York Times

And while Boulder’s level of activism may be unusual, given its liberal leanings and deep-seated concerns over climate change and the environment, the desire to take control of the electricity business is not. Officials and advocates in Minneapolis and Santa Fe, N.M., are considering splitting from their private utilities, while lawmakers in Massachusetts are trying to make it easier for towns and counties to make the break.

Over the years, many localities have examined creating municipal utilities, usually around the time their franchise agreements with private electric companies are to expire. But officials and advocates are now examining municipal utilities as concerns rise over carbon emissions from fossil fuels, especially coal, and as the ability to use renewable energy sources like solar and wind increases.

“Right now, a lot of the communities are looking at it for climate reasons,” said Ursula Schryver, director of education and customer programs at the American Public Power Association. “The biggest benefit about public power is the local control.”

But private utilities often resist giving up control — and customers — to new, public competitors, arguing that it leaves them unable to recoup investments made in anticipation of customer needs. In addition, the power industry cites its experience and long history in keeping the lights on while meeting environmental goals.

“This is our business. It’s what we do,” said David Eves, chief executive of the Public Service Company of Colorado, the division of Xcel Energy operating in Boulder. And because its parent company operates in eight states, he added, the utility can focus on being more efficient. “We don’t run other parts of the city operation and deal with those kinds of things. It’s our specialty.”

Roughly 70 percent of the nation’s homes are powered through private, investor-owned utilities, which are allowed to earn a set profit on their investments, normally through the rates they charge customers. But government-owned utilities, most of them formed 50 to 100 years ago, are nonprofit entities that do not answer to shareholders. They have access to tax-exempt financing for their projects, they do not pay federal income tax and they tend to pay their executives salaries that are on par with government levels, rather than higher corporate rates.

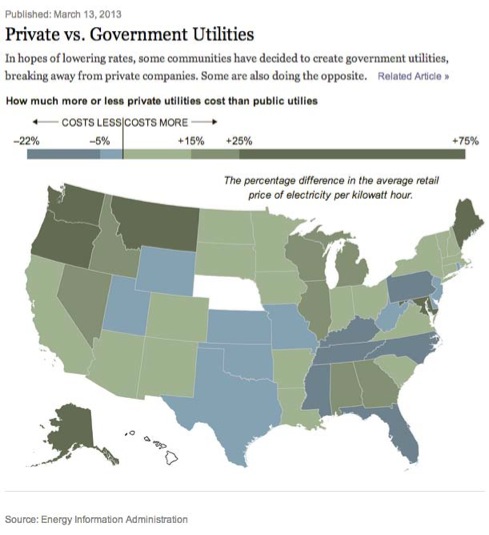

That financial structure can help municipal utilities supply cheaper electricity. According to data from the federal Energy Information Administration, municipal utilities over all offer cheaper residential electricity than private ones — not including electric cooperatives, federal utilities or power marketers — a difference that holds true in 32 of the 48 states where both exist. In addition, they can plow more of their revenue back into maintenance and prevention, which can result in more reliable service and faster restorations after power failures.

In Massachusetts after Hurricane Irene in 2011, for instance, municipal utilities in some of the hardest-hit areas were able to restore power in one or two days, while investor-owned companies like NStar and National Grid took roughly a week for some customers. According to an advocacy group called Massachusetts Alliance for Municipal Electric Choice, government-owned utilities on average employ more linemen per 10,000 customers than the private companies.

And in Winter Park, Fla., which in 2005 took over from its private utility, now part of Progress Energy, customers pay competitive rates for more reliable service, said Randy Knight, the city manager. It took time to get there: The utility lost money and raised rates in its early years while it made capital improvements to the system. But now, Mr. Knight said, it is making about $5 million in profit on about $45 million in revenue, profit that is paying to put the wires underground. The city has already buried 10 of its 80 miles of cable, a project that should be completed in the next 15 years at current rates and power supply costs.

“We’re taking the money they’re paying in income taxes and profits to the shareholders and that’s the money that we can use for these different things,” he said, adding that the city was helped by having a staff that works only in one town. “Having our, granted, smaller staff totally dedicated to our nine square miles has been so much better for us.”

But supporters of investor-owned utilities say that restoration speeds vary among government-owned and private utilities. The large electric companies, they say, are often in a better position to muster resources after storms like Sandy and Irene because they can call on extra staff from other companies and regions.

“Very few utilities can really maintain the full complement of crews and equipment that they may need — it’s not economic,” said James P. Fama, vice president of energy delivery at the Edison Electric Institute, which represents private utilities. “Municipal budgets are under pressure, just as investor-owned utility budgets are under pressure because state commissions are hesitant to pass through rate increases.”

And the road to a new utility is steep and studded with pitfalls, a long and expensive journey that has stalled many towns that have embarked upon it in recent decades. The community and the utility must fix a price for the electric company’s property, a calculation that includes not just the value of poles and wires but also so-called stranded assets, or investments made in things like power plants on the assumption of needing to provide service for a certain number of customers.

Aside from cost, towns must often battle the utility, which usually packs significant political and financial muscle. Sometimes, towns must push to change the law. In Massachusetts, the ultimate decision of whether to sell is left to the utility; lawmakers have been trying for nearly a decade to change that rule, citing high rates and the poor maintenance and performance of private utilities after storms as the main impetus.

“I don’t foresee a rush by communities to do this,” said Stephen L. DiNatale, a state representative from Fitchburg, in the north central part of the state, who recently reintroduced a bill that would require utilities to sell for the going rate if a town had the money, as determined by state regulators. “But I think having that ability to do it would help to keep some of these investor-owned utilities in line.”

Sometimes the conversion goes the other way. Colorado Springs, Colo., is studying privatizing its utility, while residents of Vero Beach, Fla., are set to vote this month on whether to sell their utility to a private company, Florida Power & Light.

And in New York, where the Long Island Power Authority was harshly criticized for its failures after Hurricane Sandy, a commission handpicked by Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo recommended privatizing the public authority, created under his father, former Gov. Mario M. Cuomo, as a successor to the Long Island Lighting Company and its Shoreham nuclear plant.

For now, though, Boulder, whose efforts are being closely watched by utilities, environmental advocates and officials across the country, is moving along even though its utility has among the best records for including clean energy, especially wind, in its portfolio. But a coal plant in Pueblo that went online in 2010 helped resuscitate a long-standing urge in the city to create an independent utility as part of an effort to reach its aggressive environmental goals.

The city just released an analysis with options for moving forward, some showing that it could get 54 percent of its energy from renewable resources and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by more than 50 percent with a government utility. If the city decides to go ahead, it estimates that forming the new utility would take two to five years.

In the meantime, the Public Service Company of Colorado is working on a plan to satisfy the city’s demands, Mr. Eves said, partly because it does not want to lose the customers, who are 4 percent of the company’s business, but also because other areas it serves have set or are designing similar energy targets.

“It’s not like we would do this just for Boulder,” he said. “It’s something that we would apply with our regulators to be able to offer it in other communities in Colorado.”

Jo Craven McGinty contributed reporting.

A version of this article appeared in print on March 14, 2013, on page B1 of the New York edition with the headline: Power to the People.