Winds Shift in Energy Debate

By ROBERT TOMSHO

June 19, 2008; Page A11

HULL, Mass. -- A recent Energy Department report said wind power could supply 20% of the country's energy needs by 2030. Community leaders in this blue-collar town of 11,000 think they might be able to top that by building an offshore wind farm that would supply all of their town's power.

That would be a first.

Nysted Offshore Wind Farm

Offshore wind turbines are common in Europe but have generated opposition in the U.S.

There are already more than 20 offshore wind farms producing electricity in Europe but, in this country, such proposals have sparked opposition from the Great Lakes states to Long Island. Opponents, including seafront homeowners, say such installations would threaten avian and aquatic life and ruin scenic vistas. With such environmental concerns pitted against the demand for clean energy, there is not a single offshore turbine anywhere in the United States.

But with energy prices soaring and climate concerns on the rise, the days of such stalemates may be numbered. Although Hull's offshore project still faces hurdles, the town's embrace of wind power reflects how local control and tangible economic benefit can diffuse such tensions and lead to broad acceptance of alternative energy sources.

A Two-Turbine Town

Since 2001, commuters on the ferry into town from nearby Boston have been greeted by the 165-foot-high wind turbine that Hull built on the shoreline next to its high school. In 2006, with little opposition, Hull erected an even bigger wind turbine on a hill overlooking one of the main roads into town. Connected to the Hull municipal power plant, the two existing turbines now provide about 13% of Hull's power needs and have kept local electric bills about a third below those of most surrounding communities.

The turbines "are one of the defining symbols of our town," says Philip Lemnios, Hull's town manager.

Onshore, U.S. wind-power capacity is growing fast, thanks to federal tax credits and new state laws encouraging the production of energy from renewable sources. In 2007, the nation's wind-power generating capacity grew by 45% to nearly 17,000 megawatts per hour, second only to Germany. Wind turbines in this country are expected to generate about 48 billion kilowatt hours of energy this year, or enough to power about 4.5 million homes.

Even so, that is only about 1.2% of the nation's demand for electricity. By comparison, wind already meets about 20% of Denmark's needs and about 12% of Spain's.

Because of favorable wind conditions and the relative ease of siting, much of the U.S. construction to date has been in areas far from big population centers. In many cases, transmission systems lack the capacity to move all of the resulting electricity to where it is most needed. "The power can't get to market," says Stow Walker, associate director of Cambridge Energy Research Associates, a consulting concern in Massachusetts.

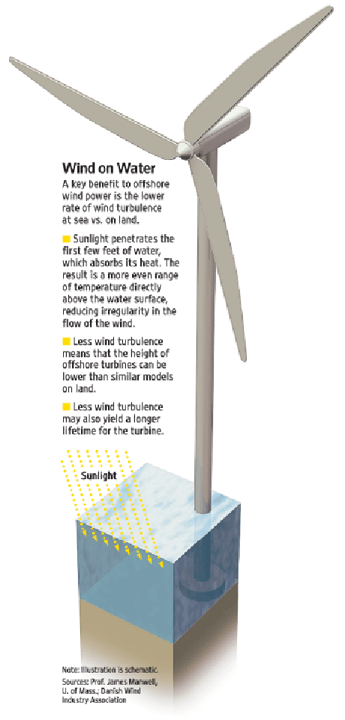

Building offshore would allow developers to produce electricity closer to big cities, particularly along the East Coast. The downside is that it would also boost construction costs by 30% or more. Erecting turbines within view of pricey coastal real estate also increases the odds of a backlash since a typical utility-grade unit includes a tower nearly as tall as the Statue of Liberty and a rotor roughly as wide as a football field is long.

Last year in New York, the Long Island Power Authority canceled plans for a 40-turbine offshore wind farm amid complaints about aesthetics and the $700 million price tag. In Massachusetts, bitter regulatory and court battles over the proposed Cape Wind project near Nantucket Island have gone on for seven years.

In contrast, when Hull officials held a public hearing last year to discuss their offshore proposal, some residents testified that they just liked to watch the existing windmills turn in the sunset; others wore T-shirts saying: "The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind."

Help from the Physics Class

A faded tourist town still known for its long, wave-swept beach, Hull sits on a peninsula that juts out into Boston Harbor like a crooked finger. Local residents have been taking advantage of wind power since at least the early 1800s, when windmills were used to make salt from sea water. In 1985, the town erected a small windmill near its high school to help generate electricity for the building. It saved the town an estimated $70,000 in energy bills over its lifetime, but was destroyed in a 1997 storm.

Soon after, a group of local citizens and teachers began lobbying town leaders to put up a new windmill at the site, with high-school physics students doing some of the planning.

Managers at the town's power plant, which is overseen by an elected board, bought into the idea and the group got advice from a renewable-energy laboratory at the University of Massachusetts.

The wind-power group held multiple public hearings and sent detailed updates out with town electric bills. From the start, the emphasis was on the direct economic benefits the turbine would provide for local residents.

At the time, the Hull power plant, with no generating capacity of its own, was buying all of its electricity from elsewhere, paying about eight cents per kilowatt hour. Planners estimated the turbine could produce it for about three cents per kilowatt hour, shaving about $185,000 a year off local utility bills and paying for operation of the town's street lights.

At public meetings, some citizens complained that the turbine would ruin the skyline and be noisy. But because local residents controlled the decision-making, opposition was minimal, says Susan Ovans, publisher of the Hull Times, a local weekly. "There was a sense that, if you had concerns, you could just go find your neighbor and ask him or her about it," she says. "It wasn't some faceless developer coming in."

Built on a strip of land where it could be seen for miles, the first turbine went up in 2001. Soon, wind-power advocates were being elected to the Hull light board and discussions began about a second installation. Citizens approved related plans at a 2004 town meeting.

"We wouldn't have a second one and be looking for more if they didn't think it was a good idea," says John MacLeod, retired operations manager of the Hull power plant and now a consultant on the offshore project.

Malcolm Brown, a retired college professor who helped to launch Hull's wind efforts, says the electricity-bill savings enjoyed by Hull residents explains the town's enthusiasm for wind power. "You can feel the flow of benefits," he says, adding that private wind-farm developers might have more success if they found ways to allow local residents to invest in their ventures.

Worries About the Skyline

As envisioned, Hull's wind farm would consist of four turbines located about a mile and a half offshore from its Nantasket Beach. Some are worried about how they will look on the skyline. "I have had people quietly express concerns," says Joan Meschino, chairwoman of Hull's board of selectmen, which governs the town. Still, at last year's town meeting, residents voted overwhelmingly to proceed with a feasibility study.

With Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick encouraging the development of wind power, the state recently gave Hull the go-ahead to conduct a detailed environmental assessment. It will, among other things, determine the precise wind and seabed conditions at the proposed site and give planners a better sense of construction costs. Early estimates are up to $40 million, roughly 10 times as much as the first two turbines combined.

Results of the assessment are expected this year. Then it will be up to Hull residents to decide whether to go ahead with the project and how to pay for it. Even if the decision is to proceed, it won't happen overnight: Because of global demand, the wait for wind turbines is approaching two years.

Electrician Patrick Cannon, chairman of the Hull light board, says he and his neighbors are proud of their wind turbines and would like to be the first to build offshore. But Hull's decision will come down to dollars and cents, he adds. "If we're going to spend ratepayers' money, they're going to want a return on investment," Mr. Cannon says. "We're not building monuments."

Write to Robert Tomsho at rob.tomsho@wsj.com